“One of the things about low prices, you generate a lot of volume. When you generate a lot of volume, you generate cash” - Craig Jelinek, CEO of Costco

Costco’s business model as a membership warehouse retailer is straightforward: sell quality merchandise at the best price. At Costco, the customer is the king, and the first thing that stands out is how the company negotiates with suppliers. As Costco has a significantly smaller number of items in a store (SKUs) than competitors, only suppliers that provide the best value proposition to the consumer win space on the shop floor. Additionally, the smaller SKU count drives higher inventory turnover. Secondly, the membership model stands out, which allows for a lower gross margin or, in the customer’s view, lower prices, and encourages customer loyalty. Lastly, Costco is obsessed with customer and employee satisfaction and brand equity. The obsession results in a highly loyal customer base, lower S&G expenses, negotiating leverage, and customers trusting Costco’s private label Kirkland Signature (Costco’s Kirkland Signature brand brought in $58 billion in sales during Costco’s latest fiscal year—equaling about a quarter of the business’s total revenue).

As Costco has continued to grow, it has leveraged its bargaining power for lower pricing—with savings passed on to its customers, the value proposition of the membership increases. Costco continues to benefit from its flywheel, which might be the stickiest and most powerful flywheel I’ve ever seen:

Return on Invested Capital

One measurement distills the effectiveness of Costco’s strategy. The Return on Invested Capital (ROIC).

Costco has consistently earned a high ROIC over the past five years. But what has caused this performance? To understand which elements of a company’s business are driving the company’s ROIC, we can split apart the ROIC as follows:

It demonstrates the extent to which a company’s ROIC is driven by its ability to maximize profitability (EBITA divided by revenues, or the operating margin), optimize capital turnover (measured by revenues over invested capital), or minimize operating taxes. So there are mainly two ways to drive a high return on capital. It’s either to have wide margins or to have high capital turnover.

Each of these components can be further disaggregated. The operating margin equals 100 percent less the ratios of cost of sales to revenues, selling and general expenses to revenues, and other operating expenses to revenues. The capital turnover combines the ratios of working capital to revenues, fixed assets to revenues, and other assets to revenues. Pretax ROIC equals operating margin times capital turnover (revenues divided by invested capital), and so on.

In 2021, Costco’s ROIC with goodwill equaled 24.2 percent. Costco has very little goodwill on its balance sheet, so the ROIC with or without goodwill is almost equal. You might ask what drives Costco’s high ROIC. As explained, Costco doesn’t mark up its costs as much as other retailers, leading to a higher cost of sales relative to revenues. It makes up for that with lower selling and general expenses. For example, its warehouse format has much lower depreciation, and its cost to stock shelves is lower because it doesn’t put items on the shelves individually but instead uses the manufacturers’ containers. Costco also sells larger sizes of its products with a smaller assortment to manage. Despite the lower selling and general expenses, it still has a lower operating profit margin than its peers. It makes up for this with higher capital productivity—primarily much lower fixed assets relative to sales. The high turnover allows Costco to generate a high return on capital (alluding to the title: “we’re not a margin company, we’re a volume company”).

The reason to compute ROIC with and without goodwill is that each ratio analyzes different things. ROIC with goodwill measures whether the company has earned adequate shareholder returns, factoring in the acquisition price. ROIC excluding goodwill measures the underlying operating performance of a company. It tells you whether the underlying economics generate ROIC above the cost of capital.

From 2015 to 2019, Costco didn’t have any goodwill, having grown entirely organically—an impressive accomplishment given its scale. But in 2020, Costco acquired the logistic firm Innovel (rebranded as Costco Logistics) for $1 billion. The acquisition allowed Costco to grow its e-commerce sales of “big and bulky” items faster. However, the purchase also meant a goodwill post was recorded on Costco’s balance sheet.

But does the decline in ROIC when measured with goodwill imply that the acquisition destroyed value? Not necessarily: cost savings and the value propositions of the acquisitions can take time to realize. Costco’s acquisition of new customers might prove easier when owning Innovel, and the expanding e-commerce opportunities may accelerate the growth.

As of FY21, Costco earned just 7% of its overall revenues through e-commerce sales. However, with Innovel, this share will likely go up as the company is deploying several initiatives to develop its web and omnichannel platform. For example, Costco is focusing on home delivery and installment of washing machines, a clever play to fend off competitors such as Amazon. Online retailing is probably Costco’s most significant threat for the next 20 years, and time will tell if Innovel will help reduce that risk.

The Balance Sheet

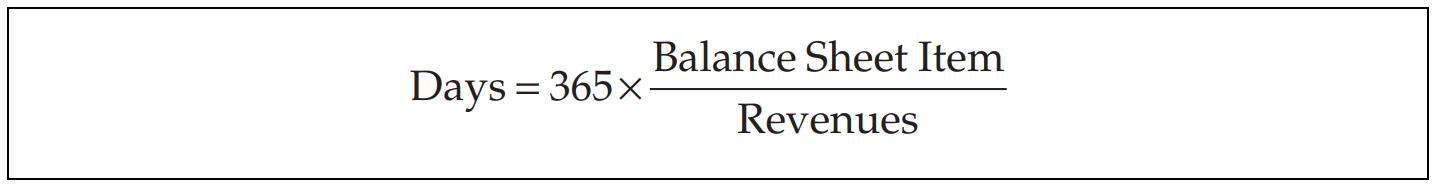

To better understand and breakdown Costco’s business, operating current assets and liabilities can be converted into days, using the following formula:

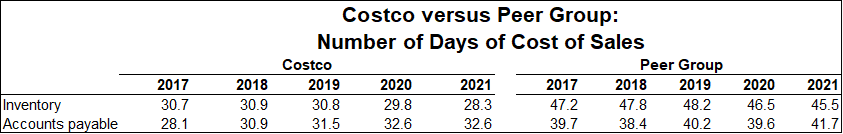

Two line items stand out when doing so: inventories and accounts payables (I relate inventories and payables to the cost of goods sold to avoid distortion caused by changing prices).

The use of days lends itself to a simple operational interpretation. How much cash is tied up in the business, and for how long? Costco’s product selection and business model result in lower inventory and accounts payable levels. In 2021, it had only 28.3 days of inventory, versus 45.5 for its peers. In other words, goods don’t stay on Costco’s shelves as long as they do at its peers’. Costco also has lower accounts payable days (32.6 versus 41.7 in 2021). This means it pays its suppliers faster, probably to get better prices. Yet again, a much smaller SKU count than competitors is feeding the flywheel of its business. Ultimately, the business model improves Costco’s negotiating leverage with suppliers for lower pricing.

Growth

Costco’s revenues have increased ~6x from $32.2 to $195.9 million between FY2000 – FY2021, representing a 21-year CAGR of ~9%. It should be noted that Costco has grown almost entirely organically (expect a couple of consolidations of JVs & acquisition of the logistics firm Innovel in 2020). The organic growth rate is attributable to: (1) the number of new stores and (2) improved per warehouse results. Between FY2000 – FY2021, Costco’s number of stores has increased by 160%, growing at a 5% CAGR, primarily attributable to its international expansion.

As seen by the chart below, in addition to increasing units, the organic revenue growth has been attributable to consistently higher per store sales. The chart provides information concerning average sales per warehouse over ten years. From the graph, it’s clear that the economics at the store level is that stores don’t mature until 8-10 years. A new store, the class of 2021 stores, will do +$140 million in revenues. But a mature store that opened in 2012 or earlier will do +$200 million. It’s fascinating that even the oldest stores have delivered per warehouse sales growth of +3% per annum over the past ten years.

Consistently increasing Revenue Per Square Foot is another way Costco has improved its per warehouse results. As shown below, since 2017, Revenue per Square Foot for Costco U.S. has increased from ~$1,000 to ~$1,400 in 2021. This is around 2.5-3 times higher square foot productivity relative to Walmart Sam’s Club.

The chart above means that people are coming more often and building bigger basket sizes. Since Costco has a much smaller SKU count than its competitors, the higher spending drives efficiencies. Additionally, the increasing Revenue Per Square Foot is attributable to value-added services such as travel, auto, and home insurance.

There is little doubt that Costco can’t continue increasing its square foot productivity. This will not only be driven by new membership signups but also by higher penetration of Executive Members (EM’s). As noted by CFO Richard Galanti on the Q2 FY21 call, EM’s doesn’t only spend more than non-EM’s but are also more loyal to the company:

For some context, EM’s pay $120 as a membership fee (as opposed to $60 paid by the other members) to get 2% (maximum of $1000) annual rewards on their purchases. They represent more than one-third of Costco’s overall customers and two-thirds of its revenues.

As shown below, the overall EM penetration (as a percentage of total paid cardholders) has significantly increased over time. The penetration of EM’s has more than doubled over the past 15 years, from 20% of paid cardholders in 2006 to 41% of paid cardholders in 2021. In the latest 10-K, Costco noted for the first time the Executive Membership mix between the U.S. & Canada and Other International. Executive members totaled 25.6 million and represented 55% of paid members in the U.S. and Canada and 17% of paid members in Other International regions. This bodes well for further international growth as Executive Membership penetration is relatively low compared to North America.

As previously noted, another way to view Costco’s long-term organic revenue growth is through the number of cardholders and the average spend per cardholder. Both metrics have contributed to the top-line growth. Since 2011, the total number of paid cardholders has increased from 35.3 million to 61.7 million. Over a more extended period, from 2000 – 2021, the average annual spend per paid cardholder had increased from ~$1,900 to ~$3,100 per year.

In summary, the takeaway from these graphs is that people love to shop at Costco.

The End Result

In the end, the number of new stores and improved per warehouse results have resulted in Costco generating a ~9% revenue CAGR. Costco’s business model has consistently produced low margins, but that is the whole point. It’s all about how little they can make off a product instead of how much. Ultimately, it’s all designed to sell a lot, which feeds the flywheel and long-term growth strategy.

Due to Costco’s solid organic revenue growth and ROIC, the company has generated substantial EPS growth. Despite a slight increase in the share count, EPS increased from $3.9 in FY12 to $11.3 in FY21–resulting in a 12.5% CAGR.

Alongside Costco’s double-digit EPS growth, the company has distributed $48 per share cumulative dividends over the past decade. That represents ~70% of its cumulative earnings over the same period. It’s easy to see that when the cash builds on their balance sheet, they pay a special dividend. Finally, while these stellar results have been achieved, the management has maintained a conservative balance sheet, using little leverage.

Expansion

One of Costco’s most promising areas for continued success is through international warehouse expansion. Despite Costco’s long history, it’s still early days for international expansion. In FY21, international sales only accounted for ~30% of Costco’s total sales. Additionally, the company currently has 256 international units, but 57% of those are units located in Canada and Mexico.

It seems as if the international expansion has been methodical, and the results have been stellar. As seen below, international comps have grown in the mid-to-high single digits over the past five years.

Replicating the Costco concept in the rest of the world has worked, given the stable international growth rate. A more specific example is Costco’s expansion in China. When Costco opened its first store in August 2019, it was so strong that the store had to suspend its business in the afternoon the same day due to being clogged up with crowds. Furthermore, on the Q3 FY21 call, the CFO noted that the company had ~400,000 members for the first store in China (for some context, the average Costco has approximately 68,000 member households per location). And the China expansion is continuing as four additional China buildings are currently underway and planned.

The big question is if international markets can reach penetration rates similar to the U.S. or Canada. The following chart is presented to give some context to the international runway. It shows how many units Costco has currently in the 12 countries where they operate, along with their respective population. It certainly seems that Costco has much more to grow.

Valuation

The graph below presents Costco and its peers’ EV/EBITDA multiples between 2005 and 2021. Although Costco traded in line with its peers from 2005 to 2011, its multiple has since increased substantially, while the multiple for its peers remained the same. I infer that Costco’s higher multiple is driven by its stronger revenue growth and enduring higher ROIC. While other valuation measures, including EV/EBITA or P/E, often provide helpful insights, the trend of the relative valuation would probably stand.

Based on the results of the last nine months, it’s highly probable that Costco will generate ~15% revenue growth and diluted EPS of at least $12.5 in FY22 (my FY22 EPS estimate is low relative to the average FactSet EPS estimate of $13.1). In the forecast period, I’ve assumed that Costco will generate similar performance to the past five years: high-single-digit revenue growth and a slight decrease in shares through repurchases, resulting in a ~8% EPS CAGR. In contrast to my estimates, Costco currently trades at ~37 NTM earnings according to FactSet estimates; in a nutshell, people like this name.

Conclusion

It was Costco’s international expansion that initially caught my attention. The company is preparing its first Swedish store in Arninge, Täby, north of Stockholm. As seen in this deep dive, international markets present a massive opportunity for Costco. While global expansion can be tricky, Costco seems to have had great success looking at international renewal rates (remember, these members are paying Costco to shop in its warehouses).

Investors should expect Costco to continue the methodical international expansion of adding ~10 net new stores per year in the foreseeable future. I see a high probability of Costco’s global markets reaching penetration rates similar to the U.S. and Canada. That would imply hundreds of more warehouses internationally—without any expansion in the U.S., Canada, or any other country in which Costco doesn’t currently operate.

At the current share price of $534, Costco is trading at ~37 NTM earnings. The company is probably reasonably priced at that valuation if low double-digit EPS growth is delivered in the long term. By no means is it a bargain, but the fact stands that the company has consistently earned higher ROIC than its peers. Additionally, the competitive moat gets deeper as the company gets bigger.

In summary, I have very little doubt regarding Costco’s long-term future. However, its valuation seems rich for the time being. Nevertheless, I acknowledge that Costco deserves a full valuation. Maybe I’m making the same mistake as Mr. Buffett:

“Costco is an absolutely fabulous organization. We should have owned a lot of Costco over the years and I blew it. Charlie was for it, but I blew it.” - Warren Buffett, Berkshire’s annual shareholder meeting in 2000

For this reason, I will keep a close eye on Costco and consider taking a position if the market ever offers a better valuation.

Nice one again Markus! Great breakdowns and metrics.

Good analysis of how well the international expansion strategy is scaling (I was barely aware, but that says more about my general retailing interest).